Stories have different kinds of narrators—some tell things linearly, some wander, some circle an unspeakable truth until they’re ready to land.

I’m partial to unreliable ones—the Holden Caulfield types who can’t be trusted to tell it straight. The ones with hidden agendas and more going on than just a neat sequence of events. They may hide their motives, but they’re often trying to tell the truth in a different way. And I suspect that when it comes to our own lives, we’re all like that. We edit. We dodge. We perform. Mostly to avoid the imagined pain of other people’s opinions.

The truth? No one actually gives a fuck. Everyone’s too busy worrying about themselves—about what others think of them, when they don’t. They really don’t. And if they do, it’s only for an infinitesimal fraction of the time you spend thinking about yourself, you solipsistic piece of shit.

Still, we hide—until something cracks.

Something insists on being told.

Did I lose you already to the infinite scroll?

This is a story about shame. About healing. About a piece of fancy paper that longed to hang on my wall.

There’s no story I’ve told myself more often than the one about my degree. You’d think I’d have it memorized by now, polished into something inspirational. But I don’t. I’m making it up as I go, processing what it means to me now.

Thanks for coming along for the ride.

I’ll begin by saying that I don’t think that fixedness helps anyone when it comes to the story of their life. The same story can land as tragedy, comedy, or transformation—depending on where you are with it. In recent years, I’d told myself that I’d moved on from the story of my degree, past its traumatic roots and the echoes of sociological critique that derive from it. But, perhaps, what I always avoided saying was: this hurt me more than I could admit.

Which is why I believe in flexible narratives: it’s the narrator that often must be able to revise himself, reedit what the past meant and reimagine what the future holds. You can rewrite everything, after all, with greater kindness, with an editor’s eye for shame, finger-pointing, and victimization, and come up with a narrative that compels in its compassion instead.

So here I am, mid-revision. Still unreliable. Still unsure of where the story ends. But finally ready to name the thing I’ve been too afraid, until now, to speak outright.

As Holden would say, I don’t want to tell you my whole goddamn autobiography, but I do want to do the therapeutic thing, convince myself that I need not be ashamed of the absurdity of my pain, and say:

I will never again see a lecture hall at Princeton University from the eyes of a freshman who had no clue what to study when there was so much to learn about the world.

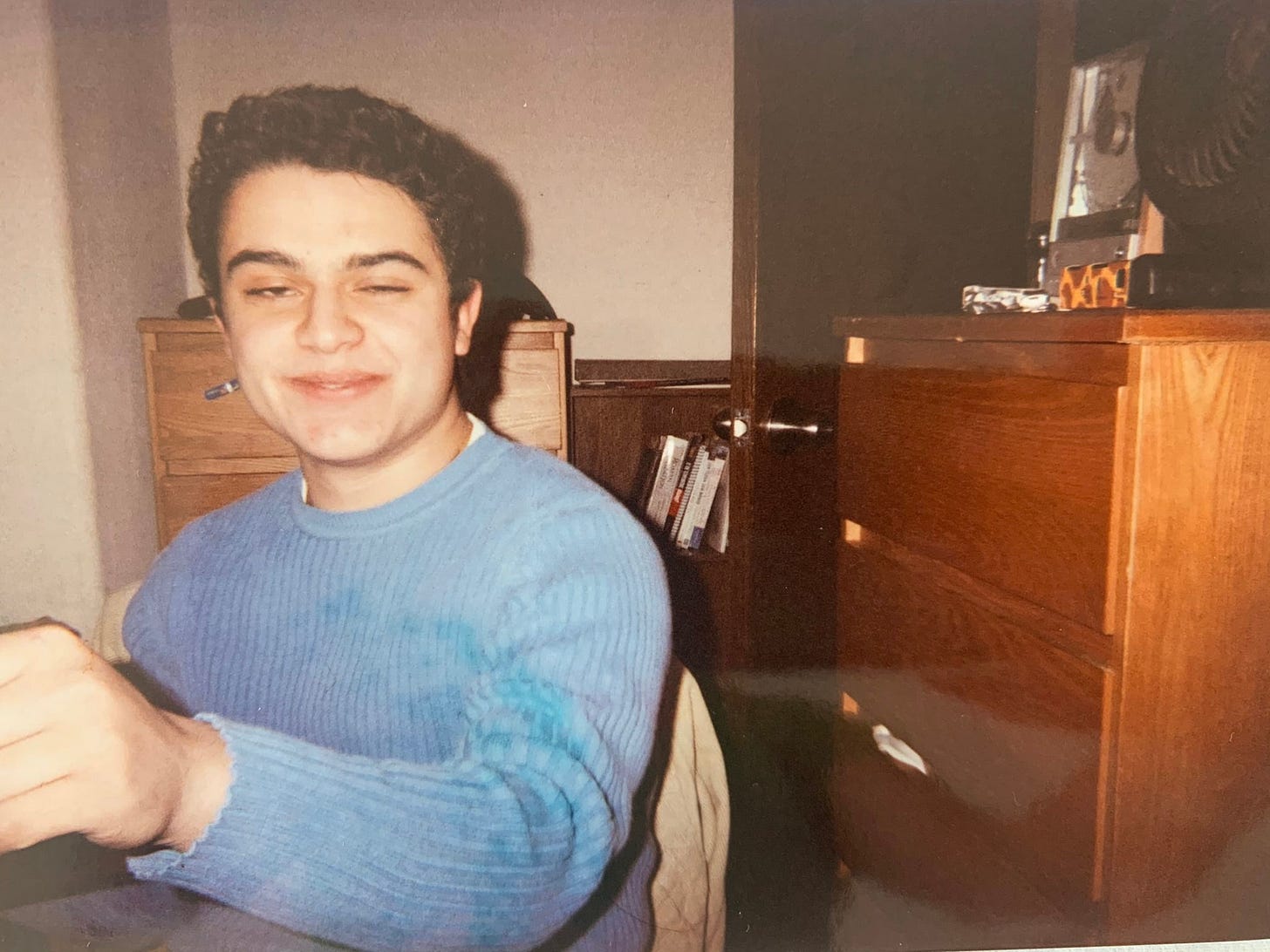

That’s where it started—under a fall sun illuminating a picture-perfect Gothic campus in central New Jersey, with a bright-eyed 18-year-old me wondering, “What will I become?”

And for years, that question haunted me—not because I didn’t become anything, but because I couldn’t let go of what I was supposed to become. What I imagined I’d become. What others thought I should become.

It hurt to not have a parchment written in Latin that declared I had completed an artium baccalaureus at the place I called home for four years.

But this isn’t about Princeton.

Or it is. But how many times can you tell your origin story before it becomes a trap? I am not that kid anymore. I’m something many years since. And I’d rather begin with who I am now—or better yet, who I’m becoming.

I could argue that my metafictional tendencies led me precisely to where I am today. All the years spent narrativizing and decoding my own story made me strangely fit to become a mental health professional. Or a bit crazy. Or both.

But with a big heart and just enough self-awareness, what I hope to be is a trusted coach to many people around the world. Someone who can help others make sense of their own lives, complicated and haphazard as they may be. Someone who can follow the thread of your story, unreliable a narrator as you may be. And if that thread leads to 🍄 or any other expanded state of consciousness—well, that’s precisely my jam.

Since 2022, I’ve trained as a humanistic therapist, gotten certified as a microdosing coach, studied psychedelic integration with ICEERS, started a small practice, and accompanied around fifty people on their healing journeys. I’ve supported others in ways that felt meaningful. I’ve nurtured my calling. I’ve shown up.

And yet, if I’m honest, I was avoiding “the issue.”

With every certificate I earned, every new modality I trained in, every “investment in myself,” I was compensating.

Not because the work wasn’t real—it was. Not because I didn’t believe in it—I did. But because part of me still carried the quiet shame of not having finished what I started. I had not, in fact, received a degree from my alma mater.

The story of why and how I didn’t finish Princeton? That’s for another post. For now, suffice it to say that I’d gotten to a point where I’d internalized the belief that I could never again aspire to the kinds of credentials I once imagined would be mine—with honors, even.

Avoiding pain explains more of our lives than we like to admit.

There are levels to this—from the clearly self-destructive (numbing out on a street corner) to the high-functioning (running Ironmans while your home life is in ruins). I’ve seen both. I’ve done neither, for the record, but I’ve had my own coping mechanisms. Thankfully, they’ve grown more life-affirming over the years.

It’s telling that I tended to my academic wound through movement and art: yoga, meditation, rock climbing, poetry, and dance. So much of my healing took place beyond the confines of rumination—beyond the mind that got me into Princeton in the first place.

And then came psychedelics, which invited me to recompose and reintegrate, to participate fully in my spiritual life in acceptance of my whole being. Something shifted then.

I realized I wanted to share my process with others—to contextualize psychedelics so others, too, might experience the kind of healing and expansion that changed my life. And to remind them to dance. To breathe. To move. To create.

I’d found my calling. I invested in coaching programs, therapy training, spiritual practice. I was learning how to show up for others and for myself. I found mentors. I deepened my knowledge. I fostered community.

And the confidence I’d gained led me to a simple, terrifying question:

If I can do all that… why not the degree?

Why not resolve the thing I’d filed under “too painful to touch”?

Why not attempt what I’d convinced myself was impossible?

Why not reclaim that part of myself—not to prove anything, but to integrate it?

So I did it.

I researched programs. I found a way to transfer my mountain of credits. I wrote essays. I paid fees. I took Gen-Eds.

I stayed up late. I drank too much coffee. I chipped away at the work, bit by bit, with the quiet determination of someone no longer trying to prove brilliance—just trying to finish something important.

I became a college student again, more than twenty years after I first became one.

I hit “submit” on my final paper at 11:25 PM on May 2, 2025. I sat back in my chair, unsure what to do when you finally end something that’s haunted you for decades.

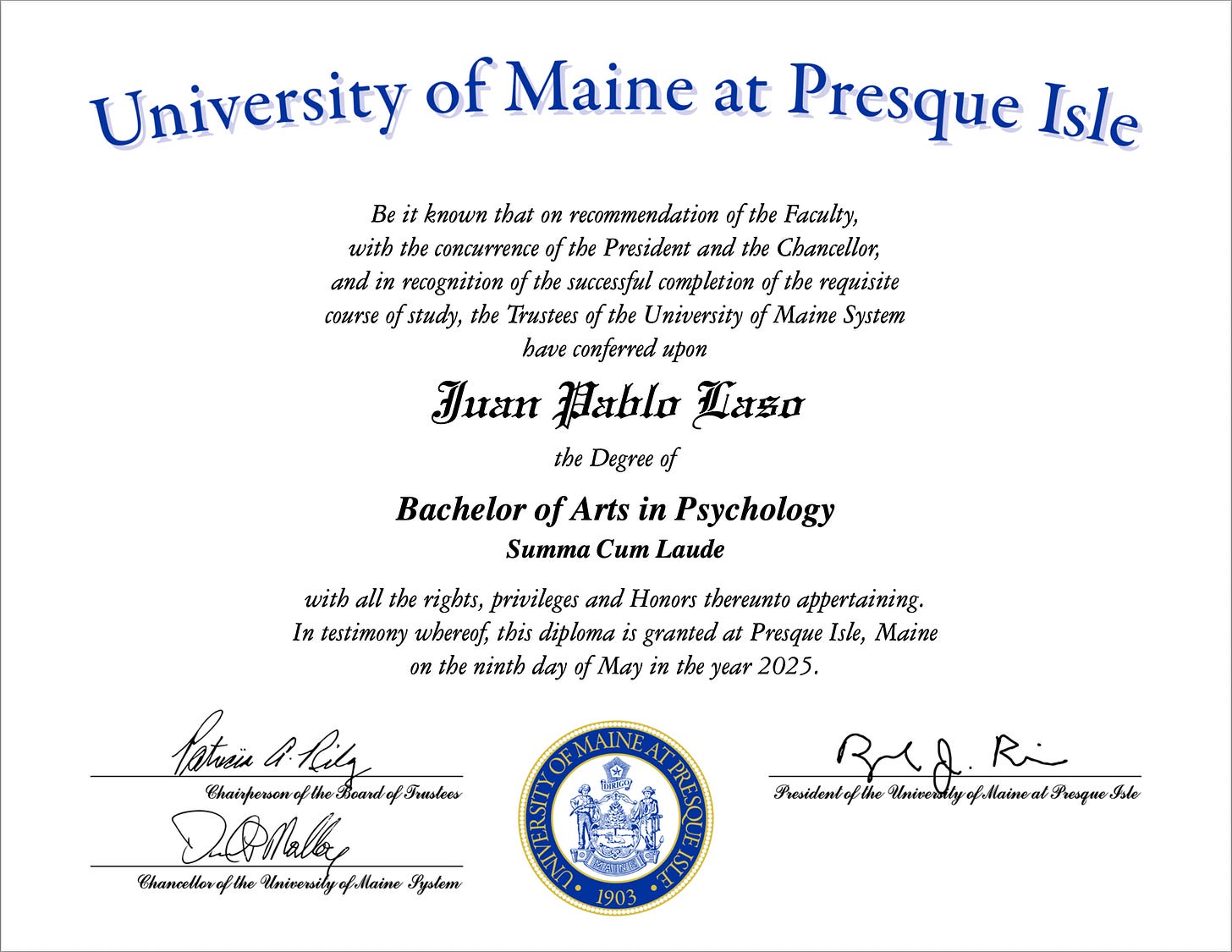

A month later, I got the confirmation: the degree had been conferred.

And today, I received the digital copy.

As of May 9, 2025, I hold a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from the University of Maine.

Ta-da.

Now, was that so hard?

YES

It felt easier to convince a postgraduate program to accept me without a degree and train me in humanistic psychotherapy. It felt easier to abscond to the middle of the Amazon jungle and consider staying there for good. It felt easier to develop a literary style.

It was one of the hardest things I’ve done in my life—not because the academics were impossible, nor because I don’t yet know how I’ll pay for it, but because I had to confront every bad habit, every fear, and the weight of my past. I had to face the years of avoidance and the self-narrative that said I wasn’t allowed to want this anymore. I had to believe I’d succeed.

I had to become something I’d never really been: a healthy college student. I had to relive the memory of having been so fucking tortured and in pain during my first attempt that I nearly lost my life.

I did this while supporting myself the way I know how today. I went to the gym. I did yoga. I saw friends. I pulled an all-nighter or two. I could’ve slept better, and maybe eased up on the carbs, but I kept it together.

And when I finally got it done… I didn’t even know how to celebrate.

There was no cap and gown. No proud parents with cameras. No inspirational speaker.

Just me. A laptop. A submission confirmation. A deep breath.

And slowly, over the following weeks, a quiet awareness began to settle.

The issue had lifted.

Two years ago, I thought this day would never come.

I wasn’t cool enough to be a college-dropout-turned-startup-founder. I didn’t have a TED Talk. I just had a painful, unresolved thing I never wanted to bring up.

But I did it.

And now, with this chapter closed, I don’t feel the need to moralize too much. I could tell you stories about how we’re all on our own timeline. About how healing and reinvention are always possible. About how letting go of who you thought you should be can make room for something better.

And all of that would be true.

But today, I just want to see something on my screen that had never been true before:

JP = college grad.

If you liked this story and want to connect, you can find me on LinkedIn and Instagram.

You can also buy me a coffee ☕️.

Reading you is truly inspiring, seeing you interact with your patients even more so. I admire you!

Beautifully written! Now I'm thinking about what lingering loose ends might eating up energy in my own life.